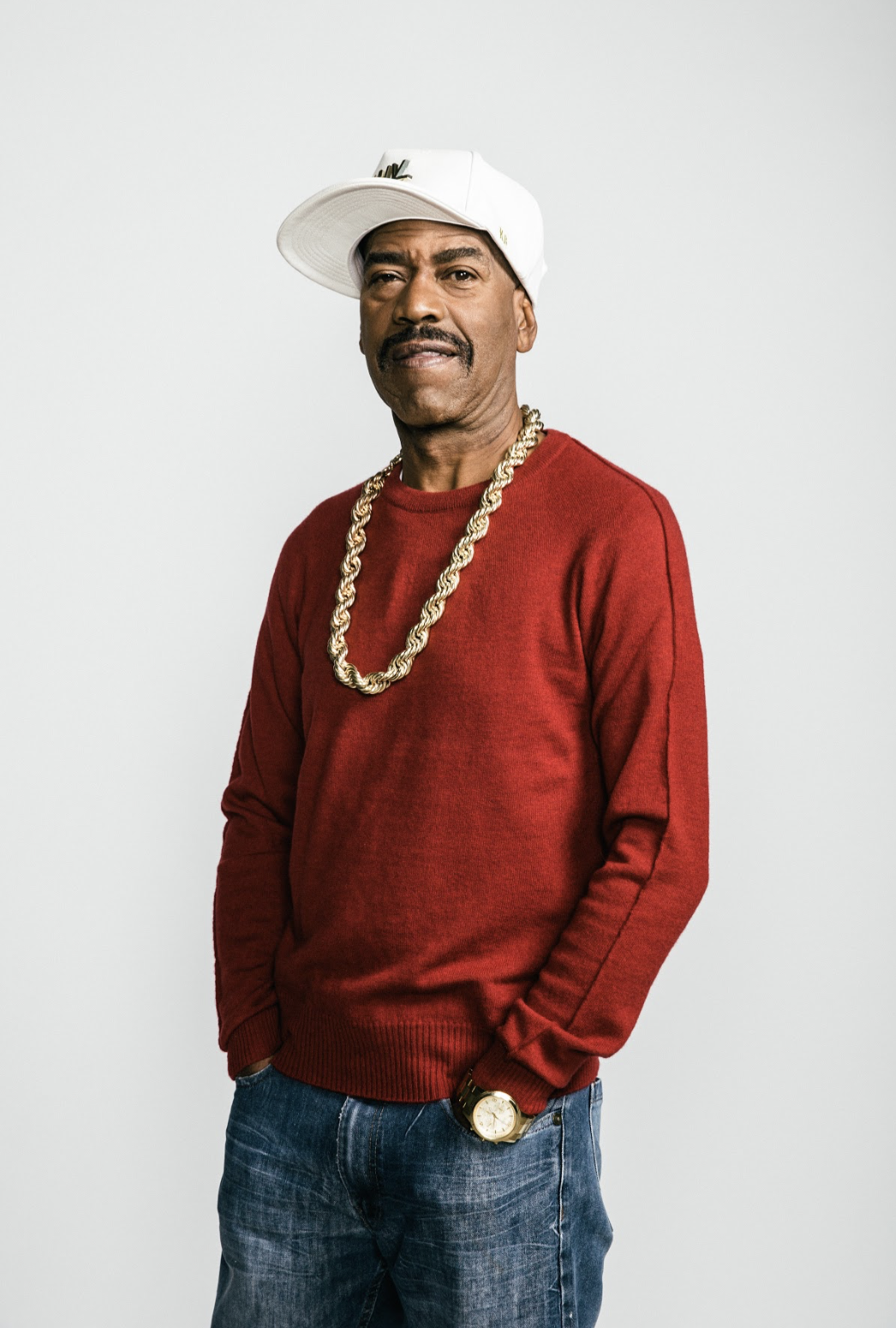

Kurtis Blow

Photo credit: GL Askew II

LISTEN TO MICROPHONE CHECK: KURTIS BLOW ON SPOTIFY.

ALSO, FOLLOW US ON SPOTIFY!

I’ve said this before — and every time I mean it — but this interview, with Kurtis Blow, is a dream come true.

It’s maybe more dreamy than most, because we’re talking about Ali being a little kid, listening to The Breaks on a fire escape and imagining what might be possible, and Kurtis Blow remembering the ’70s and ’80s as a miraculous time, the birth and the spread of hip-hop as an answer for the traumas — personal and public — of living in New York then, without a lot of money and while governed and policed by institutions and people who mean you harm.

This is a cross-generational conversation sans condescension, full of love.

It’s a very real honor that a pioneer — first rapper to sign with a major, first gold rap record, first rapper to be in a commercial, first rap music video, first rapper to use a drum machine, first rap millionaire — a forefather like Kurtis Blow would take time out of his day to sit on our couch.

Take notes.

KURTIS BLOW: Hello, everyone. I'm Kurtis Blow.

ALI SHAHEED MUHAMMAD: Kurtis Blow! Man, we're so honored to have you here. Hip-hop legend.

KURTIS BLOW: Thank you.

ALI: Forefather. Enough respect.

KURTIS BLOW: I appreciate it. Thank you. Thank you very much. It's kind of early in the morning, you know. We're doing this really, as they say, on the fly.

ALI: Yeah, it is early. It's early for us too. Shoot, I just remember growing up in New York and hearing your voice, and dreaming, really, just dreaming. I mean, "The Breaks" was like – I don't even know. I was ten years old I think at the time. Was that like 1980?

KURTIS BLOW: 1980. Yes.

ALI: Yeah.

KURTIS BLOW: It was – wow – a magical year, to say the least.

ALI: In what way?

KURTIS BLOW: I always tell people it was like a dream world. That year was awesome, incredible, just being there at the right time to have that opportunity. Because "The Breaks" was actually the first certified gold rap song. And that was my claim to fame that year.

And also being on a major label was also incredible and so important. Because not only was it documented, but I actually worked the system, that big corporation, and befriended the heads of all the different departments, like the video department, the legal department, accounting. Of course, you had the A&R department.

But promotion and publicity, that become such an important thing, of course, for not only just my career but hip-hop in general, being that we were jumping out there, being one of the first ones on a major label. So doing press and publicity and traveling and sitting up in the major office in the conference room, and they would set up interview after interview all day, from 12 to five, and I was doing that on a global level.

ALI: So you felt that they were enthusiastic? Or did they feel like everyone was charting new territories, and it was just an excitement for that? Or what was the feeling like?

KURTIS BLOW: Well, of course, I would say most people were excited and supportive. And it was fresh. And that's why I say it was more like a dream world, because everyone embraced hip-hop. Most everyone embraced hip-hop. Of course, we had a few haters, as we call them on the – "Oh, it's just a fad. It's not going to last. It's just some ghetto stuff that's happening." Or, you know, "It's not real culture." Or you even had people who were like – I'd go out there with my DJ and a microphone, people would be like, "Where's you band?" And I'm like, "Wow."

Those days were so miraculous to me, because it was mostly all good. And being that I had the experience of being an MC in the Bronx and Harlem, so I understood and it was like, I had the experience to go out there as an MC. I knew what to do to make the people have a good time, and that was very very important, being one of the first ones to reach these audiences first.

ALI: Can you talk about how you got that experience? What were the early pre-record days like?

KURTIS BLOW: Good question. And that is something that's very important to me and something I hold dear in my heart, those seven, eight years being in the Bronx and Harlem, experiencing hip-hop before it got on record. We were rapping and breakdancing and doing graffiti in New York seven, eight years before the first record came out in 1979. So back in '74, I'm, like, on the microphone on the street corners and of course the block parties and the park jams and the community centers and the house parties.

And that's how hip-hop really started out, and that was how it spread around the five boroughs of New York, from the Bronx and Harlem. It spread because people were going to those block parties and those community jams and those – I remember going out to Queens and checking out Run, Reverend Run now. He was 13. I was like 19. So this little kid was at a block party, and everyone was rocking to this 13-year-old kid, and I was like, "Wow. I gotta make you my protégé." So things like that were happening on the streets, and that's how hip-hop really really got its reputation, how it really spread, and how we got the opportunity to make records. Is because we were doing it in the streets of New York way before it got to record.

And so that's how I got my experience, going from block party to block party, going to park jam, of course all the clubs, and being in college and being "the force" in college disco, as we used to call ourselves. We had a crew called the Jedi Knights, and Mister Russell Simmons and Rush Productions and our college crew, we were deep in the promotion business, and just giving these parties where people could come out and express themselves with hip-hop.

ALI: I just want to get into your head a little bit. What were days or your nights like? In terms of, were there restless nights? Was it excitement? Could you kind of project what you were going to do the next day? Or could you not wait for it?

KURTIS BLOW: Oh, wow. Those are some fun nights. Nights with a lot of energy, being young. I remember staying up many a nights, three or four nights in a row cause I was in college, so I had college classes the next morning, but I'm a DJ, playing in the club and the club closes at four a.m. So it was like – I remember Russell Simmons, his dad – rest in peace, Mr. Simmons, Mr. Danny Simmons – he's the one that played the reverend in Krush Groove. He used to say about Russell and I, "You guys, you eat, sleep, and drink disco." Cause we were at the club on a Monday night, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday.

And we called it the track. We'd had to run the track, being promoters, and we were supporters of the hip-hop shows that were going around during that time. So it was promotional courtesy just to run the track. So we would go to Leviticus, Nell Gwynn's, Pippin's, Superstar Cafeteria, Go up to the Bronx at 371, and Executive Playhouse in Harlem with the Audubon Ballroom and Renaissance. So all of these clubs, we would run through every night. We'd go to four, five clubs throughout one night and run the track and give out our fliers for our event that would be coming up at probably the Hotel Diplomat or out in Queens at the Le Jardin or the Renaissance or Le Chalet or something like that.

But yeah, that's what it was. It was intense, because we did it every night. And then had to wake up and go to school and take tests and stuff.

ALI: Did you explain to your professors at the time what you were doing, so they would have some sort of a compassion leniency on you? Or did they just didn't understand anything you were talking –

KURTIS BLOW: That's a really good question, because I did have a conversation with one of my professors. And he's still dear to me in my heart. I have his telephone number. His name is Professor Leonard Jeffries, and he was the head of the black student department, cause we took a lot of black studies and stuff when I got to college. And he was the head professor, and so I told him, because I had taken – I had found out I had an old soul when I got to college cause I took a lot of history. He was a history professor, and so I had, like, three of his classes.

So I went to him and explained to him my life during that time as a DJ, working in two or three clubs, and when I actually got the record deal I went to him. I said, "I'm not going to take a leave of absence. It's not time yet." Russell took a leave of absence. When we made "Christmas Rap" in 1979, he left school. He needed 23 credits to graduate and left school, took a leave of absence. But I was a junior so I needed like maybe 50 or 60, and I was like, "I'm not leaving. I'm staying. I don't care. I made a hit record. It's a hit, but it's not enough for me to bank on this and just leave school," when I had this communications thing that was my dream, my real dream.

So when "The Breaks" came out in 1980, that's when I took the leave of absence. Yeah.

FRANNIE KELLEY: That was my question. So while you were doing all of this balancing nightlife and school and everything, were you thinking that music would be your career? Were you imagining –

KURTIS BLOW: Oh yeah. That's why I was in college, was because I had a plan to break into the music industry as a DJ, and then record, get a record deal, and make records, and then break into movies and do movies and produce movies, and then write books at the – I was trying to do the Paul Robeson thing actually, the whole gamut in entertainment.

But that's why I went to college, because I wanted to gain an advantage over all the competition during that time that was out there. Cause they had many MCs, like DJ Hollywood, Eddie Cheeba, Lovebug Starski, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, the Funky 4, the Treacherous Three, the Fearless Four, the Crash Crew, Cold Crush Brothers, Fantastic Five. All of these groups were coming out of the woodwork in the late '70s going into right before we made the first record, right? So it was so much competition. So I wanted to gain an advantage over them, and major in a field that I thought that was relative to hip-hop, which was communications.

As rappers, as MCs, we are the oratory. We are orators and public speakers. And I found out in college, we have so many options, so many chances, and opportunities, whether it's public speaking or journalism or broadcasting, radio broadcasting. So that's what I was trying to do, break into the music industry by being a radio DJ, and then you'll get a record deal. And so all of these things I found out in studying communications, and it gave me an advantage, a definite – I put the culture into the classroom and the classroom into the culture.

ALI: The culture. That was great. It's funny to hear you say that there was so much competition, cause I'm like, "You guys were the beginning," the alpha of what we now know is hip-hop, and this massive, global art form that's touched so many different people. I feel like now it's super competitive cause you have the entire world jockeying to get on the microphone and cut a record. But just from your perspective, that it was competitive just within the confines of New York City and that compelled you to look at the playing field and figure out how to get an edge –

KURTIS BLOW: Right.

ALI: – I'm hoping that some of the younger people who will be listening to this will be inspired by that.

There are some people who feel, well, school is overrated. And I know you have to make that individual choice, but I try to tell people like, "You really have to look at the world, that it is super competitive, and what will give you an edge. And even though you're in pursuit of your dream, I think you should wholly follow that and work to pursue it, but at the same time, just make sure you have something that's going to give you an advantage.

KURTIS BLOW: Yes. And I figured it out a long time ago that whatever it is that you want to do in your life, whatever aspirations and dreams that you do have, if you just put the practical study to it, that will ensure success rate. It'll give you better a chance. You'll have an edge for sure, and I'm living proof of it.

And I'll tell you, whatever it is, if you study the history of that subject, doctor, lawyer, businessman, rapper, whatever it is, if you study the history of it and within that history, pick a couple of people that were successful within that field that you are going after and then study the steps that they took to achieve this success, repeat those steps, and you too will achieve success. I guarantee it.

ALI: Gems.

KURTIS BLOW: I guarantee it.

FRANNIE: Well, who did you look to, considering the fact that you were pioneering a field?

KURTIS BLOW: Boom. Great question. For me, it was – I studied the history of music. The one thing that I want to say to this whole, you know, R&B – and just studying – the R&B artists that I really got into were James Brown. Number one, first and foremost, that's why I got into hip-hop. That's why I became a b-boy, a breakdancer, just trying to do his moves on the dance floor and create circles of people around me who would just watch in amazement cause I'm trying to do these James Brown moves, right?

And that cypher is still around today. You get in the cypher – DJs in the cypher, that's the competitiveness of hip-hop. MCs are in the cypher, but it started with the b-boys and breakdancing. So James Brown probably would be first and foremost my number one inspiration.

Number two I'd say would be Jimmy Castor, because he grew up a mile north of where I was born and raised in Harlem. I lived on – in a building – 465 West 140th Street, and he grew up 465 West 160th Street.

ALI: Wow.

KURTIS BLOW: One mile directly north of where I was. And he was the everything man, incredible musician, played multiple instruments. He went to the High School Of Music & Arts and I did too. I followed him and went to the High School Of Music & Arts. He's just an incredible musician, and I got a chance to meet him. I met him and told him, explained to him how much he was my hero and what he did for hip-hop. For instance, when you talk about breakdancing and the b-boys, there were songs, music, before –

ALI: Hear it in my head.

KURTIS BLOW: – we started MCing, before – I'm talking about '72, '73, the – Kool Herc – of course you've heard of him – he's the father of hip-hop. He used to play these songs that were obscure funk songs, dance music, fast in tempo, and that's when we lost our minds and did breakdancing, right?

So the first song was "Give It Up Or Turn It Loose" by James Brown. It's a live version, 1975, recorded at the Apollo. Sex Machine At The Apollo, that's the album. But that song right there became the anthem. Then I say number two would be Jimmy Castor and "Just Begun." (sings opening riff) "What we're going to do right here is go back, way back." You know, the horns come on, man. That's it. When you hear them joints, you better get ready. If I hear them still to this day, I'm like – I'm ready to go make a circle, man. I gotta go down, do my thing. Gotta do it.

So those were cats that inspired me as a b-boy. And then I had to be a DJ to play those songs in a world of disco, cause everybody else was like, "Y-M-C-A!" Donna Summer, Patrick Juvet, all the disco. You remember disco. But it wasn't as funky as James Brown's "Give It Up Or Turn It Loose" or Jimmy Castor or "Just Begun" or "Melting Pot" or "Getting Into Something" by the Isley Brothers. These obscure funk songs were so very very important, and we played them in a world of disco. And that became the hip-hop revolution or the rebellion to disco.

FRANNIE: What problem was hip-hop solving? What didn't exist that you made exist?

KURTIS BLOW: Beautiful! Great question!

FRANNIE: Thank you.

KURTIS BLOW: Well, the problems that hip-hop solved and gave us an escapism – because believe me, music is basically escapism from – we're coming out of the Civil Rights Movement and community organizers and government officials all fighting. And then you had the – I mean, it was tough times. You had the assassination, the murder of Martin Luther King in 1968 and the same year, James Brown makes "Say It Loud I'm Black & I'm Proud." So I mean, it was a rough and tough time. RFK was assassinated. We had the Vietnam War, Nixon coming in, then Watergate. And then Alex Haley with the Roots book –

ALI: Roots.

KURTIS BLOW: I mean, the TV series came out. That was huge.

So it was a time where it was really a rough and tough time. So when hip-hop came out, it was that escapism to all of the problems that were plaguing our society. The drug wars had started. I don't know if you saw the American Gangster with Frank Lucas, the Frank Lucas story. When he went to jail that was 1975, and so there was big drug wars in Harlem and the Bronx fighting for his territory and stuff, so people were dying, getting murdered every day. Gangs had started in 1972. The Warriors, that movie, it was real. That was crazy up in the Bronx. You had the Savage Nomads, the Savage Skulls, the Black Spades, the Peacemakers. I was in the Peacemakers.

And so the times were really really rough and tough, and from all of that, I grew up in Harlem around a bunch of kids who were known as the stick-up kids in Harlem. OK, that was a big thing, robberies, just crime all around us. My mom – God bless her soul – she put me in a lot of programs that deterred my involvement in all of the street things that were going on around us, and so I was in summer youth programs and sports programs and stuff like that. Ran track, played tennis, did all this crazy stuff.

Hip-hop was that real escape for us, because even though I did have problems at home with the family – my step-dad was a violent man and stuff. It was crazy. Man, I remember going out to the club just sticking my head in the speaker and closing my eyes, and the bass was so loud it rumbled through my whole body. I could feel the bass in my toes, and I was closing my eyes, and I would just go off listening to the music. And that was hip-hop. That was hip-hop.

ALI: That's, like, amazing.

KURTIS BLOW: Saved my life.

ALI: Yeah. I feel the same for me. Definitely saved my life. It was definitely escapism. I had this fire escape that I used to go out on. And I lived across the street from my elementary school, and they would set up turntables in the summertime, set up the sound systems. And I was like 6, 7, and they would just throw jams. And I would just sit out there on the fire escape and just watch what they were doing, and just listen to the music, and just dream, and just escape on the fire escape.

KURTIS BLOW: Wasn't that a beautiful, beautiful time, right?

ALI: Yeah.

KURTIS BLOW: In the summertime. That was the thing. I remember talking to one of our other pioneers – his name is DXT, very intelligent brother – and he was telling a story about – he remembered one night he was at a club, and the DJ was playing against Kool Herc. The DJ was Smoky. So Smoky didn't do that well, because Kool Herc was, like, the – I mean, he had the biggest sound system. He'd thrown on a record and get on the mic, "Turn your music down!" He'd drown you with his sound.

And so Smoky went back home that night, and he lived in an abandoned building. He put speakers out, outside the window on the second floor, and everyone went to Smoky's building, cause he told everyone, "I'm playing music outside my house." So everyone, after the party, went to around his block. So his block was full with people, and he's playing music outside his window all night long until the sun came up. And that was hip-hop. That was it.

ALI: Wow.

KURTIS BLOW: That was the escapism. Just get away from all those troubles. Forget about your troubles. Forget about your cares, man. It's going to be alright. Just listen to some good music. Let's represent. Show me what you got. We live in a world of trouble, a world of degradation, oppression, and all these buildings, abandoned buildings and being burnt down by the landlords trying to collect the insurance money. We live in all this rubble, this dirt, but we're not dirt. We are hip-hop.

ALI: That's beautiful. I'm just so grateful for all of that you guys put up with and dealt with and all the adversities you overcame in just establishing your identity, your voice, to be free.

KURTIS BLOW: Yes.

ALI: And it's just given the world so much. I know you were one of the producers for The Get Down.

KURTIS BLOW: Yes.

ALI: So was the scene you were kind of describing sort of taken from that where he was – I can't remember.

KURTIS BLOW: In the alley?

ALI: No. The DJ – agh.

KURTIS BLOW: Shaolin.

ALI: Shaolin. Thank you. When Shaolin was living in the abandoned building, and so –

KURTIS BLOW: Oh yes. Oh yes. Definitely. He took the power from the building across the way and put an extension cord, yes, that's how it went down. See, there's a documentary out about that whole time too. It's called The Bronx Is Burning. In the early '70s, New York was broke. I remember the president came here and looked at all the poor people and the degradation and all of a – the buildings up in the Bronx, they started burning them down. Every day there was a fire in the Bronx. And the building owners were doing this on purpose to collect the insurance money, so it became a scam throughout the whole city.

ALI: That's horrible.

KURTIS BLOW: And so out of all of this poverty, New York being broke, the president came here and everything, and I remember the newspaper read the next day: "The president says no to federal aid." No federal aid. This was crazy.

And so a lot of these poor people up in the South Bronx, they stayed and lived in these abandoned buildings after the landlords burnt them down, cause some of them had electricity still running through the buildings. So they jimmied the electricity, had their lights on and stuff like that, and stayed in these abandoned buildings. And this was a thing; I remember a community organizer did an article about this one time, and he was saying, "The buildings are burning down on one side of the street, but the kids on the other are trying to put something together." And that was a parable of hip-hop.

It started with the graffiti, writing on the walls, trying to paint up these abandoned buildings and make them look beautiful to say, "I live in this place. My name is John. I leave my name to carry on. Those who knew me knew me well, and those who didn't can go to hell." So we had all these little witty sayings to leave our name there. And then pretty soon we started using colored magic markers and two and three colors on a name, and then it went to the hardware store and got some spray paint and started spray painting these incredible, enormous murals, and it filtered and evolved and went on into the trains.

Oh my gosh. These guys on the trains, if you see the elevated trains in New York City up in the Bronx, the 2, the 3, the 4 train, if you're two, three, four blocks away – I mean, let's say if you're ten blocks away on 161st Street looking down towards Yankee Stadium, and you see that number 4 train go by, and it's a mural of your piece that you just painted and it's fresh, man, that's hip-hop. You could see this colorful aesthetics. We call it the aesthetics of hip-hop, is our graffiti. But just to see that elevated train with your piece on it is – that's it.

ALI: That's powerful. Where did you find the time in between DJing and going to school to be a musician? Cause that's – just in addition to being an incredible rapper, you're also –

KURTIS BLOW: The answer to that question is I'm still trying. Well, that's another thing about hip-hop that's incredible is that we use what we have that is around us to express ourselves. Talent is talent. It's God-given. But the equipment has always been something that we've never been privy to because basically we were poor kids from the Bronx and Harlem. But when you get out to Queens, that's when you get our musicians – and Brooklyn.

But for me, another side of that coin is technology, and that was my claim to fame. More so than being a musician, I used technology, like I said, the classroom and the science. So I became an avid fan of sampling and recording the DJ, and that became the sample loop, my claim to fame. I was the first to use a drum machine, and I became a master of the drum machine, making beats. "Sucker MCs" is my beat. That "boom ta-ta-ta-tah." That came from James Brown, "Escape-ism," a song called – "Excuse me, cats, while I rap! I'm about to get down. Get down!" (sings riff)

So I became a producer and just a supporter of technology and using technology. That's one thing I learned in school. So a lot of the dub mixes – I started out with the Latin Rascals and guys like that.

ALI: List them.

KURTIS BLOW: Sampling, sample loop, all of that stuff, I was the first to do that. That's my claim to fame, is bringing technology, and that was actually, I wouldn't say how I won, but just say I was competing and I was there in the competition. I don't know if I won. I was close. I was close.

ALI: Well, in comparison to what –

KURTIS BLOW: And I say that because – I gotta give a shout out to Larry Smith who was my bandleader and bass player and played bass on "The Breaks" and "Christmas Rap" and went on to produce Run-DMC.

ALI: Whodini.

KURTIS BLOW: And Whodini. And did a lot a lot a lot for hip-hop. Between Larry and myself, between myself producing the Fat Boys and of course "Games People Play" and Lovebug Starski and all of that, between Larry and myself, we actually had a little conglomerate, I would say a dynasty, in the '80s. We produced about 60, 70 percent of the rap music that was coming out during that time.

ALI: Yeah, you guys – well, when you say you think you won the competition, I'm like, I think you won as well, because your name was just larger than life, in addition to being obviously an artist, but just a producer, known as a hip-hop producer at that time. I don't recall hearing – this is me as a kid just growing up; I don't recall hearing anyone else's name more than hearing your name for all the records that you were producing or part of.

So that's why I'm asking about your musicianship, and what birthed that side of you. And the one thing that I remember is just listening to those beats, and thinking, now fast forwarding to hip-hop has been sampled and all these other forms of inspiration, but for you, I know that there were the records, but I think it would be different going in and then just writing out a song pattern and having to create something that wasn't really happening at the time.

KURTIS BLOW: Right. And I tend to look at Kanye a lot and what he said when he was talking about being a producer, and he looks at the vision of it and the colors – like, he sees colors with different songs – and when he said that I started to look at my productions that way. Some of them were fire hot red. I see some that were blue, flowing like water and just cool, and some were just really chill. I see white or white/light blue. The Christmas songs or whatever.

But just production in itself, I have to give a shout out to J.B. Moore and Robert Ford who were my first producers of my first five albums. I learned everything from them along with Larry Smith who was there as well, and then the music of Full Force, those cats, being with them and just hanging out – oh, and can't forget my DJ who was the most incredible musician. Now there's a guy that's like Jimmy Castor – or Prince plays a lot of instruments – and that's Davy DMX. He plays guitar – not only was he a DJ, but he's an excellent guitarist and drummer and keyboardist and bass, played bass on the Fat Boys "In Jail" – "Jailhouse Rap."

So being around these musicians, these excellent musicians actually motivated me and inspired me to come up with all of these hits. I had my contributions, beats and stuff. I loved making beats. As a DJ I understood what needed to be played in order for people to dance to it. So I knew about sound and my ear was just incredible as a DJ. And that's great great great things that DJs should understand, that they have an ear, so they can use that and become producers and engineers. That's their next life if they choose it. But just being around those guys motivated me.

But I also was good at making choruses and melody. I love melody, and I was a chorus master. You know like, "Fat Fat Fat Boooys." It's just simple stuff. I get that from Kool & The Gang, learning from them, and – what's the lead singer? Taylor?

ALI: James –

KURTIS BLOW: James Taylor?

ALI: No, not James Taylor.

KURTIS BLOW: What's his name?

ALI: Sorry, Mom.

KURTIS BLOW: "Ladies Night" and "Celebration."

FRANNIE: "Sorry, Mom!"

ALI: No, only because she had the crazy crush on him. How could I forget his name? I see his face and his hazel eyes right now. Did you ever meet James Brown? Of course you did. Now what was that like?

KURTIS BLOW: Yes. I met James Brown one time, and I'll never forget it, of course. It was – see, I used to work the system, being on that major label, college student. So I went to the publicity department, and I – Beverly Paige was her name. God bless you, Bev. I love you. Thank you. And I went to Bev, I said, "Bev, look. I want you to introduce me to all my heroes. I want to meet all my heroes."

So she started hooking up things. This is a big record company, PolyGram, so when they call – I'm hooking up – I did lunch with Aretha Franklin over at Hitsville. They hooked me up with Prince, La Toya Jackson, Jackson 5. Michael Jackson invited me to one of his parties at the Museum of Natural History.

ALI: Wow.

KURTIS BLOW: And I went there. I was 20 years old. Oh my god. Michael Jackson.

And so they hooked up the thing with James Brown, so it was a show. I opened up for Wilson Pickett and James Brown at the New Jersey Symphony Hall. Incredible show. I opened up for James Brown. And so I took a picture. I met him backstage and told him how much he is my hero and everything, blah blah. Took a picture. I can't find that picture anywhere.

I became friends with his son, Donald Brown, and they invited me out to the show he was at – right before he died, passed away, he invited me to a show New Year's Eve at B.B. King's in New York City. I was going. It was about – and then he passed away like two days after Christmas or something like that. But I was going out to hang with the family. I would like to say –

Oh, I'm working on a documentary about James Brown and his inspiration to hip-hop.

FRANNIE: That's dope.

KURTIS BLOW: All those stories I told you about, 1968 and all that stuff, and man, the b-boys loved him. We all were trying to be James Brown. All of that stuff, we're going to put it in a documentary, and we're working with the James Brown Family Foundation and his daughter Deanna Brown-Thomas. And so we're going to shoot a tribute to him on his birthday, May 3, coming up 2019.

ALI: Wow. That's incredible.

KURTIS BLOW: Yup, yup. Big shout out, and rest in peace to Venisha Brown. She just passed away.

ALI: Just passed away, yeah. Man, there's so much.

FRANNIE: Can I ask a question about this way that because you signed the first deal with a major, first rap music video, all these things, that your career represents this move of hip-hop into the mainstream?

KURTIS BLOW: Yes. Many people call me hip-hop's first superstar. I don't –

FRANNIE: First millionaire. First rap millionaire.

KURTIS BLOW: You know, I really – I understand. But it's part of my humility and just trying to be modest – because you have to walk around in this body, and I'm like, "God bless me. Thank you. Thank you, Jesus. Thank you all of my friends and my family and everyone who helped me." But if there would be one thing, one title, that I would say, I would say that, yeah, I have the first commercial, first national commercial.

FRANNIE: Right. The Sprite commercial. Right.

KURTIS BLOW: So it's incredible. It's awesome. The stats, I have the stats, right?

FRANNIE: Yeah, you do. You do.

KURTIS BLOW: You have to understand it's miraculous. God could've chosen Grandmaster Melle Mel. God could've chosen Ice T or LL Cool J or Run-DMC, for that matter. But I was there at the right time, at the right place and the right time. And why? But why? These are the unexplainable things that we all need to look at and say, "God did it."

FRANNIE: Right, right. I mean, I can see the hand of God in a choice like that, because it's actually a dangerous position – or it's – when hip-hop moves into the mainstream, it's in danger by the forces of –

KURTIS BLOW: Of evil. Yes, and sometimes –

FRANNIE: Essentially yeah. We're talking about money. We're talking about people taking things, taking credit, using things for nefarious purposes.

KURTIS BLOW: How about just the haters of hip-hop?

FRANNIE: Yeah.

KURTIS BLOW: At one point, I was – I hate to say this. I really shouldn't say this. But at one point I was thinking, when John Lennon was murdered, what can stop somebody from just thinking about me in that manner? So there is – at least I'm aware. I'm not scared, but I'm aware it could happen. I've thought about it, but I gotta live my life like I'm thankful that I'm here. So that's more fun.

FRANNIE: Right. Yeah.

ALI: And almost maybe to add on to what you were saying, to be such a – to be an example –

FRANNIE: Right. Exactly.

ALI: – of someone who has humility, who's had great success, but also walks with humility and reverence for the creator.

KURTIS BLOW: And that education thing is big.

ALI: And the education, yeah. So it's like, you're an example, I think, for the generations to – you can look at the obvious, I guess, stars and the lures of the life that is acquired from the success and the wealthy success aspect and from the focus point of the media and all that, you can look at that as an example to be an inspiration of, like, why you go into the studio, or you can look at someone who, like yourself, who has achieved so much, but still you walk even-keeled, like I said, with reverence for the creator.

KURTIS BLOW: Amen.

ALI: And there's such a balance of the human spirit and a lot of love that just vibrates off of you. And I think that for those who – cause sometimes the kids don't do their history, and you mentioned earlier that it's really important to do the history for something that you're going to pursue. But for those who do take the time and can look and have a couple of inspirations, I'm looking at you and I see so much. I identify so much with your path, and I'd rather a Kurtis Blow than – and I won't mention any others to – I'm not trying to put negativity on other people, but I'd just rather be a vision of love, and –

KURTIS BLOW: There you go.

ALI: – someone who has taken the art form to really connect people. And still to this day, you're still a part of pushing the art form and the genre forward. I think the creator – I mean, the creator does what the creator does. We just follow suit if we choose pay attention or not.

KURTIS BLOW: Well, thank you. That's beautiful. If there ever was a compliment I wanted to hear, it would be definitely I want to be noticed and remembered as being a man of God. And I think you hit it home right here. So really, that is why I'm still here, is because God wills it. Believe me. I mean, it could've been many instances in my path where God has raised me from the dead, and literally God did that.

Two years ago, I went into cardiac arrest.

FRANNIE: Oh no.

ALI: Wow.

KURTIS BLOW: And I died for five minutes, and thank God my son was there, and he begged the police to do CPR, and the ambulance came. When they came, they hit me with the bop gun, and I came back. And when I got to the hospital, my wife of 34 years came and she just prayed. The doctors were like, "Look, he had a massive, massive heart attack!" Later they changed it, went into cardiac arrest. "He had a massive heart attack, and he had a clogged artery. We gotta go in and do open heart surgery, and we don't know if you're going to make it!" I'm like – my wife just started praying right there. All the doctors stopped. It just seemed like everything just paused when she was praying.

Then the doctor who told me I needed the operation, he was sitting at the monitor. He looked at the monitor and did a double-take, looked at her, looked at the monitor, jumped up and ran out of the room. My wife ran after him and found out, she told me later, that, "Oh, he doesn't need an open heart surgery, but we're still going to go up– the clogged artery is gone. He's fine. But we're still going to go up and look around in the heart and see if there are any abnormalities or anything."

So that procedure was going to take two hours, so they roll me in. And then I prayed. She told me later. The doctor came back 15 minutes later. So she was thinking, "Oh my God. My husband died. My husband died." And no, he said, "Oh no, he's fine! He's great. Your prayers were answered." So the power of prayer was with us, and it was God's will that I stayed alive, cause not many people come back from cardiac arrest. And I had all my faculties, no kidney failure, no problems. It's like, wow. Just a miracle.

So the miracle of life is for real, and God is for real. He's a facilitator –

ALI: Indeed.

KURTIS BLOW: – of who is here and who he brings home. Amen. So I'm a walking testimony of that, and I will be until the casket drops. And that's why I'm here. Amen.

ALI: Thank you for sharing that.

FRANNIE: Can we talk about what you do with the life that you have? So this production that you're doing, the Hip-Hop Nutcracker, so that's another way that sort of – that you maybe perpetuate hip-hop culture in these spaces that have in the past denied entry to hip-hop culture.

KURTIS BLOW: Amen. Yeah.

FRANNIE: And I think about things like Hamilton, Broadway and the way that, I've written about this before, those spaces need hip-hop way more than hip-hop needs it. But what do you hope to achieve by doing something like this tour?

KURTIS BLOW: Well, there are a couple of I would imagine wishes or missions associated with the Hip-Hop Nutcracker. We've been at it for five years now. Yes, it's a great look for hip-hop.

FRANNIE: OK.

KURTIS BLOW: It's a great look for hip-hop to be in these venues, these top-of-the-line venues, with these audiences of multicultural people, all ages. I see grandparents bringing their sons and their sons bringing their sons. Three generations come out. I see all kinds of countries, all kinds of races again.

But you know what? There's a more important agenda with the Hip-Hop Nutcracker I'm finding out in the last three years, which is this spirit of love that we are presenting with the Nutcracker play itself. And it is the holiday season. It's all about Christmas, the birth of Christ, right? But it's Happy Hanukkah, of course, and Kwanzaa, and we say shalom to all our Israel brothers. But it's all about the spirit of love that's in the air during Christmastime.

OK, it's the birth of Christ, but it's really about reaching to your family and your friends and your loved ones to say thank you for putting up with you all year, right, right? It's the time to remember all our fallen heroes who have fallen throughout the year, and it's really about buying a gift and giving a gift to someone that you love to say thank you. And that's the spirit. That's that joy, that joy, that spirit of love that's in the air during Christmastime, that we want to present. It's our agenda to bring that across to the audiences and make them feeling good when they leave the play. So that's our job.

And I always tell MCs, "The real job of an MC is that we are entertainers. Hip-hoppers, all of them, whether you're a DJ, whether you're a b-boy, whether you're at a concert, at a club, your job is entertainment, to make the people feel good inside. And when they leave your concert, when they leave your performance or your show, they should be feeling good inside." That's our ultimate job.

FRANNIE: What does hip-hop give the Nutcracker that it didn't have before?

KURTIS BLOW: Hip-hop gave the Nutcracker the relevance of modern day society. So here we have Tchaikovsky and this classic play with classical music. Mind you, I'm a fan. I love classical music. I mean, orchestras, this is music theory. When you learn music in school, the science of music, you study orchestras. You have to know all of these instruments. As a matter of fact, we're trying to raise money for a music program at a school in Harlem, and they need some brass horns and tubas and stuff. But just to have this fusion and connection and to bring hip-hop to fuse and connect with classical music to me is boom.

Because I actually – when I first got started four or five years ago, there was a song by Nas that came out. They took it off the radio, but I loved the song. It was him and Diddy called "You Can't Stop Me Now."

ALI: Oh yeah. "Can't Hate Me Now."

FRANNIE: "Hate Me Now?"

ALI: Yeah.

KURTIS BLOW: Remember the orchestra sound and that big-sounding thing? And during that time there was a style of hip-hop going around, and I call it, like, king's music or royalty music. And I would probably record an album calling it The Return Of The King and use that kind of sound for maybe four or five songs.

But just that is one of the good parts, and the fact that hip-hop is now fusing with classical music, and I'm an avid supporter of fusion and hip-hop fusion of course. First to do country and western rap with "Way Out West" and rock 'n' roll rap.

FRANNIE: And go-go.

KURTIS BLOW: And go-go music. Branding and networking with other forms of music is important to hip-hop. It's showing that it's for everyone, and it's malleable. You can shape it in any form. So that's one thing.

And then the other hip-hop brings is, like I said, the relativity of being the number one music of today. It's the number one music on the globe, on the face of the planet. And 25 percent of all music streamed is hip-hop. And so we're now stepping into new arenas and bringing this culture to the masses, to where it belongs, for everyone. And that is so important, not only to hip-hop but to music in general, just entertainment.

FRANNIE: So this idea that hip-hop belongs with the masses, some people feel like it should be more in a private setting, within the community, that there's some – it's possible for dilution to happen or for it to be – its messages confused or twisted. Was that ever a concern for you?

KURTIS BLOW: No, because I know it's malleable, like I said.

FRANNIE: It's strong enough.

KURTIS BLOW: It's strong enough. We have variety. We have a lot of flavor, mad flavor, we call it, from – of course we always have our conscious rappers, representing from Common to Talib Kweli and even Nas, people like that. Future and Kendrick Lamar bringing the new trap sound with of course the Migos and Lil Boosie. We have our mad flavor. We have the West Coast style. We have the Dirty South. We have people over in Chicago, St. Louis. It's a lot of flavor, a lot of different variety and styles that we could bank on.

But there needs to be a balance of course. At one point there was, I would say, too much gangster rap. Now I see a lot more conscious rap. Kendrick Lamar for instance has brought back some real conscious stuff, and makes you sit down and listen to his songs and rewind for the lyrical content, instead of the profanity. So I think we'll be alright. We've been around for 40 years now, and we've had many styles and flavors come and go. But it's always been a creative thing and a spiritual thing, I think, the way these styles come. And I support it, so yeah. We're good.

ALI: Can you speak to the challenges that females rappers that you may have noticed when you were coming up and the landscape at that point and where it is in comparison to where it is now?

KURTIS BLOW: I – being a male rapper, maybe I have not looked at the women of hip-hop as closely as I should throughout the years, but as far as I'm concerned, they have the greatest potential, because they are women. And I'll tell you why. And it goes back to seeing this in contest and just competition, and if there're a group of rappers, if you have five, six, seven guys in a contest, and there's one female, that one female most of the time, I say 90 percent of the time, will come in top three in that category, only because of the uniqueness of female being involved in this competition. So you have the potential of really doing some – eyes will be open if you go out there and pursue it.

So I want to motivate all the women. We need more, we need more females in hip-hop. The doors are open. Take a look at Cardi B. She's doing her thing. From her – Nicki has been doing her thing. MC Lyte, big shout out to her. Going all the way back to Sha-Rock, the first lady. I mean, women have been representing, but they have been doing a great job whenever they're there. We just need more. We need more.

I remember seeing the Funky 4 + 1 More, 1981. She's like – Funky 4 + 1 More.

ALI: Plus 1 More.

KURTIS BLOW: She's the one more. And she's in the middle of these four guys, right, and they had two DJs. These guys are rocking it, but she comes out and tears them all up. Everybody. Consistently every night she was the best rapper, female rapper I've ever seen, but she was the best rapper of that group by far. You don't want to go on after Sha-Rock.

FRANNIE: Yeah, if you gotta compete that hard just to be there.

KURTIS BLOW: Yeah.

FRANNIE: And the uniqueness of the perspective also, it's like, going to say things differently and talk about things differently. Yeah.

KURTIS BLOW: Exactly.

FRANNIE: Yeah, we do need more.

ALI: We need more to come sit on this couch, this uncomfortable couch. Anyway.

FRANNIE: I know. No, I – this has been incredible, totally incredible.

KURTIS BLOW: But I would like to shout out, from NJPAC, Mr. David Rodriguez and Eva, Julia, Tracy, Josh, everybody working so hard. I mean, this is our fifth year. I really really feel special about being a part of the team with Jennifer Weber, the choreographer, and all of the dancers, the b-boys and b-girls who are out there representing. They give 150 percent just to have b-boying, b-girling, the culture, fusing with ballet and the choreography and the classical music together. And we have a violinist that comes out and gets down with the DJ, so it's an incredible show.

I really think that it's worthwhile and something for everyone to see how hip-hop really is a great musical art form. It's a great great culture. It's America, and you need to come see it at the top of the line. Cause I think of this play as being the top-of-the-line for hip-hop. It gets no better, other than a Jay-Z concert or a P Diddy with all the pyrotechnics. But yes, I just want to shout out NJPAC and everybody. Lil Boosie, my buddy I just met.

And the museum! We're working on this project called the Universal Hip-Hop Museum. We've been at this for five years now. Big shout out to Rocky Bucano and Dedra Tate, Adam Silverstein and Ed Young and everyone. Renee Foster. All of our people. Reggie Peters.

FRANNIE: And that's in the Bronx, right?

KURTIS BLOW: That's going to be in the Bronx, opening the doors 2022. We start construction next year, 2019. We just raised 20 million, four million from the city of New York, city council, about five million from the state, and then we have an LOI from our contractors, our building contractors, for 12 million to start construction. And we're going to be in the Bronx Point section of New York City, which is three blocks south of Yankee Stadium.

ALI: Wow.

KURTIS BLOW: Right? Big shout out to the museum. If you want to find out more about that, uhhm.org is the website. Please make a donation. And then we have the Hip-Hop Nutcracker, for the tickets and schedule, hiphopnutcracker.com.

ALI: Great. Thank you so much.

FRANNIE: Thank you so much for coming here.

KURTIS BLOW: Alright.

ALI: For everything, not just for just coming to Microphone Check. Obviously we're grateful for that, but just for everything that you've done.

KURTIS BLOW: Thank you guys. Thank you.

FRANNIE: You made –

ALI: Yeah, this –

FRANNIE: – us.

ALI: There couldn't be A Tribe Called Quest, there couldn't be an Ali Shaheed Muhammad, if there wasn't a Kurtis Blow. So thank you so much for just everything.

KURTIS BLOW: Thank you. My pleasure. You guys, take care. Keep doing what you're doing. Keep representing. You guys, we need more outlets like this.

FRANNIE: Yeah.

KURTIS BLOW: For our hip-hop people, for our music people. Cause music is culture, man. It's something that really really calms the savage beast at times, and it motivates us. It inspires us. It makes us feel good inside, and it's supposed to. So let's keep representing that good stuff.

ALI: Indeed.

KURTIS BLOW: Thank you.

FRANNIE: Yes, sir. Thank you.

ALI: Thank you.